On Survivor 41, players were presented with the opportunity to take a “shot in the dark” on immunity at Tribal Council. This last-ditch effort was represented by dice. One might have imagined the players rolling said dice, praying for it to land on a side signaling their safety. Alas, the dice were instead placed in a contraption, which then revealed whether the player received their one-in-six chance at safety.

Elsewhere in the season, eventual winner Erika Casupanan was presented with the hourglass twist, through which she could reverse the course of the game. The twist was appropriately represented by an actual hourglass. Less appropriately, Erika did not act on her decision to activate the twist by turning the hourglass upside down (as anyone who has ever used an hourglass is wont to do) but instead by smashing it.

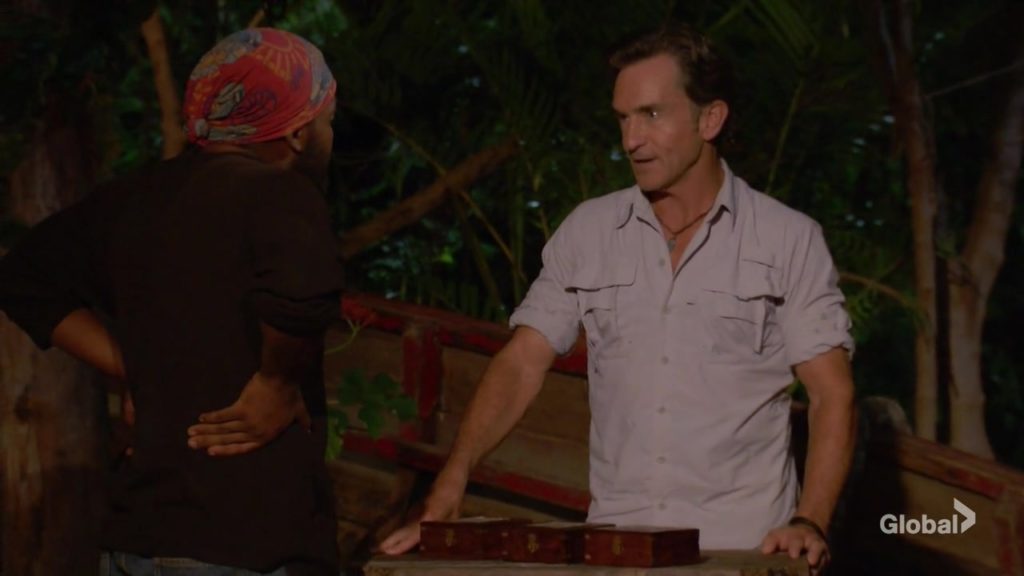

This kind of imprecision marked (or is it marred?) the whole of Survivor 41. Showrunner and host Jeff Probst adorned the latest season with plenty of bells and whistles, but with little thought to how these ornaments may actually impact the experience for both players and viewers alike. That the trinkets representing these additions to the game barely operated like their real-life counterparts was par for the course in a season where the goal seemed to be rendering viewers as confused as a goat on AstroTurf.

In Survivor 41, merges were no longer merges and wins were no longer wins. And with players losing votes, gaining votes, risking votes, and swapping votes, monitoring the events of Survivor 41 was a nearly futile task.

Survivor 41 was billed as the toughest iteration across the show’s 20+ years on television. Indeed, players were given very little food or resources. But this season may have been the toughest in Survivor history for an entirely different reason. For all its constant tinkering, Survivor, for the most part, has always been a balanced competition. But for the first time in the show’s history, Survivor gave up all pretense of being fair.

Nothing represented the game’s imbalance better than Liana Wallace’s Knowledge is Power advantage. This advantage is far from the first misstep in Survivor’s history, but it does mark an alarming turning point for the show, in which Jeff and his fellow producers are willing to place their feet on the scales of power. Liana’s advantage allowed her to steal another player’s idol or advantage at Tribal. To use it, she simply had to ask another player whether or not they had such a power in their possession, and they could not lie in return. Anyone who has seen even a single episode of Survivor may have just heard a bell go off in their head.

They can’t lie? They can’t LIE?! It boggles the mind that a bunch of longtime Survivor producers could have gathered in a meeting room and signed off on a twist that strips players of their most basic right in the game. Survivor is a social strategy game, and deceit has been at its core since its inception in 2000. Survivor 41 attempted to limit its players’ agency in a variety of ways (several castaways couldn’t even vote for the first several episodes), but manipulating the actual social fabric felt like a step too far.

To be fair, Xander Hastings — the eventual target of Liana’s advantage — managed to outmaneuver its excessive reach to brilliant effect. He found a way to deceive Liana despite the advantage’s attempt to nullify any such opportunity. In effect, Xander not only outplayed Liana, but he outplayed Survivor as well.

There were other examples of the producers unfairly impacting the game this season. Danny McCray and Deshawn Radden were none too pleased when the results of the merge immunity challenge were inexplicably reversed by Erika’s easy decision to smash the hourglass. And Deshawn later faced the wrath of the “Do or Die” twist, in which he was nearly eliminated due to a game of chance. Interestingly, Deshawn misplayed the Monty Hall problem that determined his fate yet still managed to keep his torch alive. The moment admittedly led to some compelling TV, but it would have been a rather disgusting result had Deshawn left the game without a single vote cast against him.

Complaining about something like fairness can come across as childish. What is fair anyway? One could easily write off Danny and Deshawn’s frustrations; after all, they signed up for a game known for its twists and turns. But games do carry with them an implicit agreement upon a set of rules, and when those in power manipulate and alter those rules as they see fit, the implications could stretch well beyond the game at hand.

Netflix’s hit Korean drama series Squid Game exploited this idea rather overtly. It tells the tale of a shadowy organization that gathers hundreds of desperate South Koreans to compete in a series of children’s games for money, leaning into that all-too-childish notion of fairness.

The stakes in Squid Game couldn’t be higher. Failure to complete a task results in death, after all. To the Front Man’s credit, however, he and his masked henchmen establish a clear set of rules early on and continually make efforts to reinforce such rules in the name of fairness. Of course, even this bit of equality is soon undermined, as Squid Game reveals itself to be less about the desperation enacted by life under late-stage capitalism and more about the cruelty of those overlooking it all.

When players pair off for the fourth game, Mi-nyeo is left unchosen. Players and viewers alike might expect her to die as a result, and she is whisked away to confirm as such. But when the game’s surviving players return to their quarters only to see Mi-nyeo is alive, it comes as a surprise to us all. The Front Man keeps Mi-nyeo alive, a small twist in the game that portends much more sinister ones to come. As players’ expectations are subverted, the Squid Game reveals itself to be an unreliable format.

To win the Squid Game, one must engage in a bit of gamesmanship, something our protagonist Gi-hun must grapple with over time. This pressure-cooker environment is played out for the pleasure of passive onlookers, wealthy American elites who place bets on and pick favorites from the game’s several participants. By extension, the games play out for our pleasure as well. We are the ones watching the show. No matter how much we might wince, Squid Game is there for us, and we are implicated in its events.

Isn’t Survivor much of the same? The show may feature real people, but as long as they are inside our television screens, they are edited characters. And no matter how much Jeff may try to humanize his show’s characters by bantering with them before challenges or showing brief glimpses of their lives back home, his willingness to run them through his wide assortment of trinkets and toys suggests the contrary.

Since the show premiered in 2000, Survivor‘s appeal has been — at least to some extent — rooted in our fascination with what people may be willing to do for $1 million. It has led to many a debate about the ethics of lying, swearing on your loved ones, etc. Throw in the fact that these people are often cold, starving, homesick, and dirty, and you have yourself a winning formula!

Indeed, all game shows and reality competitions stem from a sort of sick capitalist obsession. Like its peers, Survivor has largely outgrown this interest, but its latest season was an uncomfortable reminder of the show’s ultimate goal: to make the best TV possible. I think I’ve made it clear whether or not I believe the show has followed through on even that simple promise, but the sentiment remains. Jeff and company have grown alongside their players over the years. Still, they remain in an elevated position, willing to put these players through the wringer with little regard for fairness and equality.

I’ll stop short of equating Jeff with Squid Game’s Front Man (I’d hate to hide those dimples under a mask), although I’d be more than happy to lump in the show’s creator and executive producer Mark Burnett with those slimy VIPs.

Fortunately for Survivor, even at its worst, it is among the best shows on television. Unfortunately for those of us demanding more from the show we cherish so dearly, there may not be much impulse to change anytime soon.

Written by